On the dance floor, Quinn moves with confidence – strong, focused and fully in her element. The music kicks in, her feet find the beat and, in that moment, the world narrows to a sparkle. It’s hard to imagine that the same heart carrying her through rehearsals and performances once faced overwhelming odds before she was even born.

When Quinn’s mother, Sandee Walker, walked into her anatomy scan in 2017, she expected to leave with a simple memory of finding out the gender of her third baby. She brought her two sons along, certain they were about to meet their baby sister for the first time.

Instead, the ultrasound technician paused. “She said, ‘I need to go get the doctor,’” Sandee recalled. “I knew immediately something was wrong.”

In a room that was supposed to hold joy and anticipation, Sandee felt everything change. That moment marked the beginning of Quinn’s journey – one defined by resilience, faith and a heart that would have to work harder than most from her very first days of life.

Learning Quinn’s heart would need special care

Doctors soon confirmed that Quinn had hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS), a rare and complex congenital heart defect in which the left side of the heart does not fully develop. Sandee remembers how quickly everything moved after that, including appointments, information and decisions that filled Sandee’s and her husband’s mind.

“They didn’t go into great detail,” she said. “They just said we needed to be seen immediately by a cardiologist from Phoenix Children’s.”

Further testing showed Quinn was otherwise healthy. The plan became clear: Sandee would deliver Quinn and, shortly after birth, her daughter would be transferred to Phoenix Children’s for specialized heart care.

Before Quinn was even born, Sandee and her husband met with the pediatric heart surgery team at Phoenix Children’s to understand what the road ahead could look like. In those early conversations, they met Daniel Velez, MD, Co-Director of the Center for Heart Care and Division Chief of Cardiothoracic Surgery at Phoenix Children’s. Just as important as the care plan was the feeling they walked away with: they weren’t going to face this journey alone.

“Meeting and working with Dr. Velez was the best thing to happen to us, hands down,” Sandee said. “Dr. Velez is the kindest soul I think I’ve ever known. He’s not just Quinn’s heart surgeon, he’s gone above and beyond for us.”

From the start, Dr. Velez wanted Quinn’s family to know this journey can take twists and turns – and that they would never have to navigate them alone. “With many HLHS patients it’s usually never a straight line to success,” he said. “It’s always up and down.”

Six days old and facing open-heart surgery

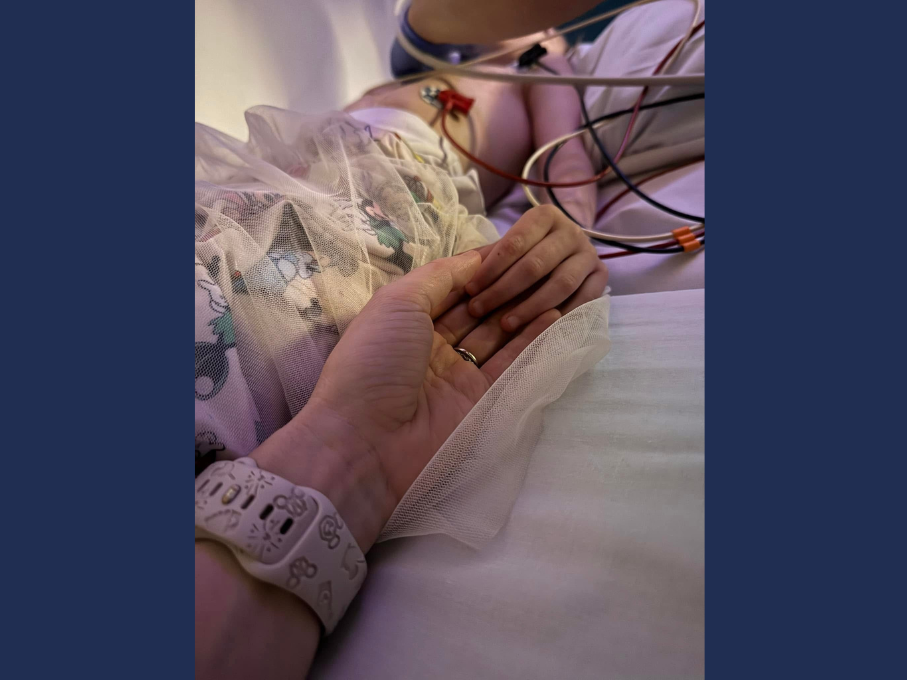

Quinn was transferred to Phoenix Children’s when she was 2 days old. At just 6 days old, she underwent open-heart surgery – the first of three complex procedures required to treat hypoplastic left heart syndrome.

That first surgery, called the Norwood procedure, is often the toughest, most challenging part of the journey. “It’s hardest to recover from the first surgery,” Dr. Velez said. “The heart gets tired, and if this happens, heart transplant becomes an option.” During the Norwood procedure, surgeons repair and enlarge the aorta and place a small tube called a shunt to help blood flow from the heart to the lungs so it can pick up oxygen.

“After the first surgery, she wasn’t recovering like the team had hoped,” Sandee said. “Quinn was really sick.”

Sandee remembers one moment as clear as yesterday. “I remember Dr. Velez coming in and saying, ‘We need to just leave her alone. We’re going to do everything on Quinn’s time.’” And that’s what they did. Everyone gave her space, watched her closely and waited. “Quinn started recovering, she had a miraculous turnaround after that,” Sandee said.

After a month in the hospital, Quinn was strong enough to go home, though “home” looked very different than her parents had imagined. “We basically had an intensive care unit set up in our living room,” Sandee said.

Sandee and her husband became Quinn’s around-the-clock caregivers, managing medical equipment, medications and constant monitoring as they helped her recover and waited for her next surgery.

Learning how to eat – and grow

At 4 months old, Quinn returned to Phoenix Children’s for her second open-heart surgery, a Glenn operation. In this procedure, surgeons remove the shunt from the first surgery and connect a large vein that returns oxygen-poor blood from the upper body directly to the blood vessel leading to the lungs. This helps blood flow to the lungs more efficiently and reduces some strain on the heart.

For Dr. Velez, timing matters just as much as technique. “Each step is done at a time when baby can tolerate it,” he said.

Afterward, Quinn spent weeks in the cardiovascular intensive care unit. During that time, she needed a feeding tube because she was too tired to eat by mouth and wasn’t gaining enough weight. “That was really hard for us,” Sandee said. “It’s so hard to see your child not do normal things like eating or hitting milestones like crawling or sitting up.”

Once Quinn recovered and came home, she began intensive feeding therapy at Phoenix Children’s – a demanding program that required hours of therapy, five days a week. Sandee stepped away from her job for a year to focus entirely on Quinn’s care. “We were determined,” she said. “It was hours a day and the program was so successful.”

In just a few months, Quinn went from taking no food by mouth to eating everything on her own. After a year without needing her feeding tube, it was removed. That moment was a milestone they still treasure.

With feeding therapy behind her, Quinn moved on to physical therapy and quickly began catching up on other milestones. She even walked before her first birthday.

A third surgery and a different kind of healing

At 3 years old, Quinn returned for her third and final planned open-heart surgery – a major milestone for children living with HLHS. This time, it happened during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“That was the scariest situation we’ve ever been through,” Sandee said. “I had to hand our child off to surgery by myself. I’ll never forget crying in the elevator with a security guard.”

Quinn’s recovery took time – and it asked something different of her than physical healing alone. After years of procedures and hospital stays, she was diagnosed with medical post-traumatic stress disorder. “She was very scared of everyone,” Sandee said. “She didn’t trust anyone except Dr. Velez.”

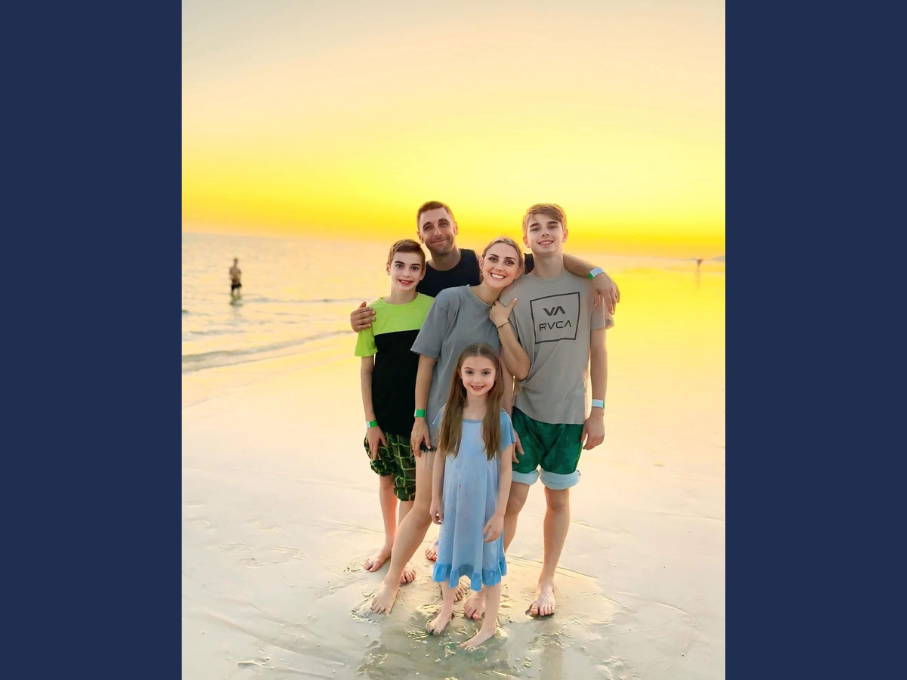

Dr. Velez understood that trust was part of Quinn’s healing, too. “I’m privileged to see how she has developed as a person from a newborn,” he said. She’s progressed from those earliest days to talking, laughing and growing into herself.

Even then, care didn’t stop at surgery. With support from Phoenix Children’s, Quinn began play therapy and gradual exposure therapy to help her feel safe again in medical settings, practicing the small steps that once felt impossible.

“We celebrated milestones that nobody ever thinks about,” Sandee said. “Like letting a doctor check her pulse or getting on a scale without fear.”

After the third stage, children like Quinn continue with long-term follow-up. Dr. Velez said Phoenix Children’s Fontan Clinic brings a multidisciplinary team together to help patients stay healthy and to recognize early when a child needs extra support.

Finding freedom on the dance floor

Before Quinn was born, Sandee asked one question that mattered deeply to her. “I’m a dance teacher,” she said. “I always wanted a little dancer.”

Early on, Sandee heard plenty of cautions about what life with a complex heart condition might look like. including whether dance would ever be possible. “They were very wrong,” she said.

Quinn started dancing at 2 years old – sometimes with her oxygen tank nearby – and never looked back. Today, she’s a competitive dancer who spends most of her free time at the studio.

“All of her cardiologists tell me there’s something about dance that keeps her heart healthy and strong,” Sandee said. “I’m so grateful we pushed for her.”

For Dr. Velez, those moments are the reason he does this work. “If you’re able to look at social media that mom shares, I tear up with Quinn doing dance and seeing her thrive,” he said.

Dr. Velez isn’t surprised. “The world is their oyster,” he said of children born with complex heart conditions. “You do the best you can with what you have. You may slow down. It may look different. But that’s not stopping.”